Sketch Art Images How Do I Become a Christian

The delineation of Jesus in pictorial form dates back to early Christian art and architecture, as aniconism in Christianity was rejected within the ante-Nicene catamenia.[1] [2] [3] [4] It took several centuries to reach a conventional standardized form for his physical advent, which has afterward remained largely stable since that time. Most images of Jesus have in common a number of traits which are now about universally associated with Jesus, although variants are seen.

The conventional image of a fully disguised Jesus with long hair emerged effectually Advertising 300, but did not become established until the 6th century in Eastern Christianity, and much subsequently in the West.[ commendation needed ] It has always had the reward of beingness hands recognizable, and distinguishing Jesus from other figures shown around him, which the use of a cruciform halo besides achieves. Before images were much more varied.

Images of Jesus tend to bear witness indigenous characteristics similar to those of the culture in which the image has been created. Beliefs that certain images are historically authentic, or take caused an administrative status from Church tradition, remain powerful among some of the faithful, in Eastern Orthodoxy, Anglicanism, and Roman Catholicism. The Shroud of Turin is now the best-known example, though the Image of Edessa and the Veil of Veronica were meliorate known in medieval times.[ not verified in trunk ]

In that location is only i clarification of the concrete appearance of Jesus given in the New Testament, which is in the Book of Revelation 1:12-16.

Early Christianity [edit]

Earlier Constantine [edit]

Except for Jesus wearing tzitzit—the tassels on a tallit—in Matthew 14:36[5] and Luke 8:43–44,[6] there is no physical description of Jesus contained in any of the canonical Gospels. In the Acts of the Apostles, Jesus is said to have manifested every bit a "light from sky" that temporarily blinded the Apostle Paul, just no specific form is given. In the Volume of Revelation in that location is a vision the author had of "someone like a Son of Man" in spirit form: "dressed in a robe reaching down to his anxiety and with a gilt sash around his chest. The hair on his head were white like wool, and his eyes were like blazing fire. His anxiety were similar burnt bronze glowing in a furnace (...) His face was like the sun shining in all its brilliance" (Revelation 1:12–16, NIV). Employ in art of the Revelation description of Jesus has generally been restricted to illustrations of the book itself, and zip in the scripture confirms the spiritual form'southward resemblance to the physical form Jesus took in his life on Globe.

Exodus twenty:4–half dozen "Thou shalt not make unto thee whatever graven image" is one of the Ten Commandments and made Jewish depictions of first-century individuals a scarcity. Just attitudes towards the interpretation of this Commandment changed through the centuries, in that while starting time-century rabbis in Judea objected violently to the depiction of human being figures and placement of statues in Temples, third-century Babylonian Jews had unlike views; and while no figural art from first-century Roman Judea exists, the art on the Dura synagogue walls developed with no objection from the Rabbis early in the third century.[vii]

During the persecution of Christians nether the Roman Empire, Christian art was necessarily furtive and cryptic, and there was hostility to idols in a grouping notwithstanding with a large component of members with Jewish origins, surrounded by, and polemicising against, sophisticated pagan images of gods. Irenaeus (d. c. 202), Clement of Alexandria (d. 215), Lactantius (c. 240–c. 320) and Eusebius of Caesarea (d. c. 339) disapproved of portrayals in images of Jesus.[ citation needed ] The 36th canon of the non-ecumenical Synod of Elvira in 306 Advertizement reads, "It has been decreed that no pictures exist had in the churches, and that which is worshipped or adored be non painted on the walls",[8] which has been interpreted past John Calvin and other Protestants every bit an interdiction of the making of images of Christ.[ix] The event remained the field of study of controversy until the end of the 4th century.[ten]

The earliest surviving Christian art comes from the late 2nd to early 4th centuries on the walls of tombs belonging, most likely, to wealthy[xi] Christians in the catacombs of Rome, although from literary bear witness at that place may well have been panel icons which, like nearly all classical painting, take disappeared.

The Healing of the Paralytic – i of the oldest possible depictions of Jesus,[12] from the Syrian city of Dura Europos, dating from about 235

Initially Jesus was represented indirectly by pictogram symbols such as the ichthys (fish), the peacock, or an anchor (the Labarum or Chi-Rho was a later development). The staurogram seems to have been a very early on representation of the crucified Jesus within the sacred texts. Later personified symbols were used, including Jonah, whose three days in the abdomen of the whale pre-figured the interval betwixt Christ'south death and resurrection; Daniel in the panthera leo's den; or Orpheus charming the animals.[13] The image of "The Good Shepherd", a beardless youth in pastoral scenes collecting sheep, was the most common of these images, and was probably not understood as a portrait of the historical Jesus at this flow.[fourteen] It continues the classical Kriophoros ("ram-bearer" figure), and in some cases may as well represent the Shepherd of Hermas, a pop Christian literary piece of work of the 2nd century.[15]

Among the earliest depictions clearly intended to directly correspond Jesus himself are many showing him as a infant, ordinarily held past his female parent, specially in the Admiration of the Magi, seen every bit the offset theophany, or brandish of the incarnate Christ to the world at large.[16] The oldest known portrait of Jesus, plant in Syria and dated to about 235, shows him as a beardless boyfriend of administrative and dignified begetting. He is depicted dressed in the style of a immature philosopher, with close-cropped hair and wearing a tunic and pallium—signs of skilful breeding in Greco-Roman lodge. From this, information technology is evident that some early on Christians paid no heed to the historical context of Jesus being a Jew and visualised him solely in terms of their own social context, as a quasi-heroic figure, without supernatural attributes such as a halo.[17]

The appearance of Jesus had some theological implications. While some Christians thought Jesus should have the beautiful appearance of a young classical hero,[xviii] and the Gnostics tended to retrieve he could modify his advent at will, for which they cited the Coming together at Emmaus as evidence,[19] others including the Church building Fathers Justin (d. 165) and Tertullian (d. 220) believed, following Isaiah:53:2, that Christ's appearance was unremarkable:[20] "he had no form nor comeliness, that nosotros should wait upon him, nor dazzler that nosotros should delight in him." Simply when the pagan Celsus ridiculed the Christian organized religion for having an ugly God in nearly 180, Origen (d. 248) cited Psalm 45:3: "Gird thy sword upon thy thigh, mighty one, with thy beauty and fairness"[21] Later the emphasis of leading Christian thinkers changed; Jerome (d. 420) and Augustine of Hippo (d. 430) argued that Jesus must have been ideally beautiful in confront and body. For Augustine he was "beautiful as a child, cute on globe, beautiful in heaven."

From the 3rd century onwards, the first narrative scenes from the Life of Christ to be conspicuously seen are the Baptism of Christ, painted in a catacomb in nearly 200,[23] and the phenomenon of the Raising of Lazarus,[24] both of which tin can be clearly identified by the inclusion of the pigeon of the Holy Spirit in Baptisms, and the vertical, shroud-wrapped body of Lazarus. Other scenes remain ambiguous—an agape feast may be intended as a Last Supper, but before the development of a recognised physical appearance for Christ, and attributes such as the halo, it is incommunicable to tell, equally tituli or captions are rarely used. There are some surviving scenes from Christ'south Works of nigh 235 from the Dura Europos church building on the Persian frontier of the Empire. During the 4th century a much greater number of scenes came to be depicted,[25] usually showing Christ equally youthful, beardless and with short hair that does not reach his shoulders, although there is considerable variation.[26]

Jesus is sometimes shown performing miracles by means of a wand,[27] as on the doors of Santa Sabina in Rome (430–32). He uses the wand to change h2o to wine, multiply the bread and fishes, and raise Lazarus.[28] When pictured healing, he just lays on hands. The wand is thought to be a symbol of ability. The bare-faced youth with the wand may signal that Jesus was thought of every bit a user of magic or wonder worker by some of the early Christians.[29] [xxx] No fine art has been found picturing Jesus with a wand before the 2nd century. Some scholars suggest that the Gospel of Marker, the Secret Gospel of Mark and the Gospel of John (the so-called Signs Gospel), portray such a wonder worker, user of magic, a sorcerer or a Divine human being.[31] Just the Apostle Peter is likewise depicted in aboriginal art with a wand.[xxx]

Another depiction, seen from the tardily 3rd century or early 4th century onwards, showed Jesus with a beard, and within a few decades tin can be very shut to the conventional blazon that later emerged.[32] This depiction has been said to describe variously on Imperial imagery, the type of the classical philosopher,[33] and that of Zeus, leader of the Greek gods, or Jupiter, his Roman equivalent,[34] and the protector of Rome. According to art historian Paul Zanker, the bearded type has long hair from the start, and a relatively long beard (contrasting with the brusque "classical" beard and hair always given to St Peter, and well-nigh other apostles);[35] this delineation is specifically associated with "Charismatic" philosophers like Euphrates the Stoic, Dio of Prusa and Apollonius of Tyana, some of whom were claimed to perform miracles.[36]

After the very earliest examples of c. 300, this depiction is mostly used for hieratic images of Jesus, and scenes from his life are more likely to use a beardless, youthful blazon.[37] The trend of older scholars such as Talbot Rice to encounter the beardless Jesus as associated with a "classical" artistic style and the bearded one as representing an "Eastern" one drawing from aboriginal Syria, Mesopotamia and Persia seems impossible to sustain, and does not feature in more recent analyses. Equally attempts to relate on a consistent footing the explanation for the type chosen in a item piece of work to the differing theological views of the time have been unsuccessful.[38] From the 3rd century on, some Christian leaders, such equally Cloudless of Alexandria had recommended the wearing of beards by Christian men.[39] The centre departing was also seen from early on, and was as well associated with long-haired philosophers.

Christ as Emperor, wearing military dress, and crushing the serpent representing Satan. "I am the style and the truth and the life" (John 14:6) reads the inscription. Ravenna, later 500

After Constantine [edit]

From the middle of the 4th century, after Christianity was legalized by the Edict of Milan in 313, and gained Royal favour, at that place was a new range of images of Christ the King,[twoscore] using either of the 2 concrete types described to a higher place, just adopting the costume and often the poses of Imperial iconography. These adult into the diverse forms of Christ in Majesty. Some scholars reject the connection between the political events and developments in iconography, seeing the alter as a purely theological ane, resulting from the shift of the concept and championship of Pantocrator ("Ruler of all") from God the Father (yet not portrayed in fine art) to Christ, which was a development of the same period, perhaps led past Athanasius of Alexandria (d. 373).[41]

Another depiction drew from classical images of philosophers, often shown as a youthful "intellectual wunderkind" in Roman sarcophagii; the Traditio Legis image initially uses this type.[42] Gradually Jesus became shown as older, and during the 5th century the image with a beard and long hair, now with a cruciform halo, came to boss, peculiarly in the Eastern Empire. In the earliest large New Testament mosaic wheel, in Sant'Apollinare Nuovo, Ravenna (c. 520), Jesus is beardless though the menstruation of his ministry until the scenes of the Passion, after which he is shown with a beard.[43]

The Good Shepherd, now clearly identified as Christ, with halo and often rich robes, is still depicted, as on the apse mosaic in the church building of Santi Cosma e Damiano in Rome, where the twelve apostles are depicted as twelve sheep below the imperial Jesus, or in the Mausoleum of Galla Placidia at Ravenna.

Once the disguised, long-haired Jesus became the conventional representation of Jesus, his facial features slowly began to exist standardised, although this process took until at least the sixth century in the Eastern Church building, and much longer in the West, where make clean-shaven Jesuses are mutual until the 12th century, despite the influence of Byzantine fine art. Merely by the late Middle Ages the beard became almost universal and when Michelangelo showed a clean-shaven Apollo-like Christ in his Last Judgment fresco in the Sistine Chapel (1534–41) he came nether persistent attack in the Counter-Reformation climate of Rome for this, too as other things.[44]

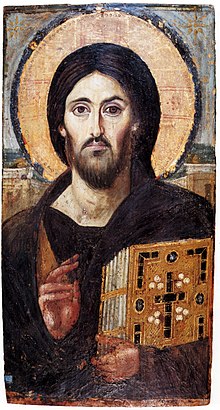

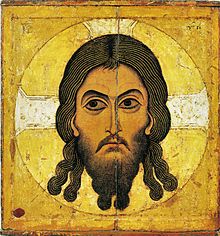

French scholar Paul Vignon has listed xv similarities ("marks", like tilaka)[45] between most of the icons of Jesus after this bespeak, especially in the icons of "Christ Pantocrator" ("The all-powerful Messiah"). He claims that these are due to the availability of the Epitome of Edessa (which he claims to exist identical to the Shroud of Turin, via Constantinople)[46] to the artists. Certainly images believed to accept miraculous origins, or the Hodegetria, believed to be a portrait of Mary from the life by Saint Luke, were widely regarded as authoritative by the Early on Medieval flow and greatly influenced depictions. In Eastern Orthodoxy the grade of images was, and largely is, regarded every bit revealed truth, with a status almost equal to scripture, and the aim of artists is to re-create earlier images without originality, although the mode and content of images does in fact change slightly over time.[47]

As to the historical advent of Jesus, in i possible translation of the apostle Paul's First Epistle to the Corinthians, Paul urges Christian men of first-century Corinth not to have long pilus.[48] An early commentary by Pelagius (c. Advertizing 354 – c. AD 420/440) says, "Paul was complaining because men were fussing about their hair and women were flaunting their locks in church. Not only was this dishonoring to them, merely information technology was also an incitement to fornication."[49] Some[ who? ] have speculated that Paul was a Nazirite who kept his pilus long[ citation needed ] even though such speculation is at odds with Paul's argument in I Corinthians 11:xiv that long hair for men was shameful at the fourth dimension. Jesus was a practicing Jew and then presumably had a beard.[ citation needed ]

Later on periods [edit]

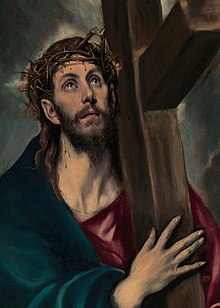

By the 5th century depictions of the Passion began to appear, mayhap reflecting a change in the theological focus of the early on Church.[l] The 6th-century Rabbula Gospels includes some of the earliest surviving images of the crucifixion and resurrection.[fifty] By the sixth century the bearded delineation of Jesus had go standard in the East, though the Westward, especially in northern Europe, continued to mix bearded and unbearded depictions for several centuries. The depiction with a longish face up, long straight dark-brown hair parted in the middle, and almond shaped eyes shows consistency from the 6th century to the present. Various legends developed which were believed to authenticate the historical accuracy of the standard delineation, such as the image of Edessa and later the Veil of Veronica.[51]

Partly to aid recognition of the scenes, narrative depictions of the Life of Christ focused increasingly on the events celebrated in the major feasts of the church building calendar, and the events of the Passion, neglecting the miracles and other events of Jesus' public ministry, except for the raising of Lazarus, where the mummy-like wrapped trunk was shown standing upright, giving an unmistakable visual signature.[52] A cruciform halo was worn simply by Jesus (and the other persons of the Trinity), while plain halos distinguished Mary, the Apostles and other saints, helping the viewer to read increasingly populated scenes.[52]

The period of Byzantine Iconoclasm acted as a barrier to developments in the East, but by the 9th century fine art was permitted once more. The Transfiguration of Jesus was a major theme in the East and every Eastern Orthodox monk who had trained in icon painting had to prove his craft past painting an icon of the Transfiguration.[53] However, while Western depictions increasingly aimed at realism, in Eastern icons a depression regard for perspective and alterations in the size and proportion of an image aim to attain beyond earthly reality to a spiritual significant.[54]

The 13th century witnessed a turning point in the portrayal of the powerful Kyrios prototype of Jesus every bit a wonder worker in the West, as the Franciscans began to emphasize the humility of Jesus both at his birth and his decease via the nativity scene equally well equally the crucifixion.[55] [56] [57] The Franciscans approached both ends of this spectrum of emotions and as the joys of the Nativity of were added to the agony of crucifixion a whole new range of emotions were ushered in, with wide-ranging cultural affect on the image of Jesus for centuries thereafter.[55] [57] [58] [59]

After Giotto, Fra Angelico and others systematically developed uncluttered images that focused on the depiction of Jesus with an ideal human beauty, in works like Leonardo da Vinci's Last Supper, arguably the outset Loftier Renaissance painting.[60] [61] Images of Jesus at present drew on classical sculpture, at least in some of their poses. However Michelangelo was considered to take gone much as well far in his beardless Christ in his The Terminal Judgment fresco in the Sistine Chapel, which very clearly adjusted classical sculptures of Apollo, and this path was rarely followed by other artists.

The High Renaissance was gimmicky with the start of the Protestant Reformation which, especially in its beginning decades, violently objected to almost all public religious images as idolatrous, and vast numbers were destroyed. Gradually images of Jesus became acceptable to nigh Protestants in various contexts, especially in narrative contexts, as book illustrations and prints, and afterward in larger paintings. Protestant art continued the now-standard depiction of the physical appearance of Jesus. Meanwhile, the Catholic Counter-Reformation re-affirmed the importance of art in assisting the devotions of the faithful, and encouraged the product of new images of or including Jesus in enormous numbers, also continuing to use the standard depiction.

During the 17th century, some writers, such as Thomas Browne in his Pseudodoxia Epidemica criticized depictions of Jesus with long hair. Although some scholars believed that Jesus wore long hair considering he was a Nazarite and therefore could not cut his hair, Browne argues "that our Saviour was a Nazarite after this kind, nosotros take no reason to determine; for he drank Wine, and was therefore called by the Pharisees, a Wine-bibber; he approached also the dead, every bit when he raised from expiry Lazarus, and the girl of Jairus."[62]

By the terminate of the 19th century, new reports of miraculous images of Jesus had appeared and go along to receive significant attention, e.g. Secondo Pia's 1898 photograph of the Shroud of Turin, i of the virtually controversial artifacts in history, which during its May 2010 exposition it was visited by over two million people.[63] [64] [65] Another 20th-century depiction of Jesus, namely the Divine Mercy image based on Faustina Kowalska's reported vision has over 100 million followers.[66] [67] The first cinematic portrayal of Jesus was in the 1897 film La Passion du Christ produced in Paris, which lasted 5 minutes.[68] [69] Thereafter cinematic portrayals have connected to show Jesus with a beard in the standard western depiction that resembles traditional images.[seventy]

A scene from the documentary film Super Size Me showed American children existence unable to identify a common depiction of Jesus, despite recognizing other figures similar George Washington and Ronald McDonald.[71]

Conventional depictions [edit]

Conventional depictions of Christ developed in medieval art include the narrative scenes of the Life of Christ, and many other conventional depictions:

Mutual narrative scenes from the Life of Christ in art include:

- Birth of Jesus in art

- Adoration of the Shepherds

- Admiration of the Magi

- Finding in the Temple

- Baptism of Jesus

- Crucifixion of Jesus

- Descent from the Cantankerous

- Last Judgement

Devotional images include:

- Madonna and child

- Christ in Majesty

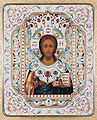

- Christ Pantokrator

- Sacred Heart

- Pietà (mother and dead son)

- Lamb of God

- Human being of sorrows

- Pensive Christ

Range of depictions [edit]

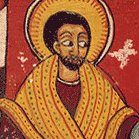

Certain local traditions have maintained different depictions, sometimes reflecting local racial characteristics, every bit exercise the Catholic and Orthodox depictions. The Coptic Church of Egypt separated in the fifth century, and has a distinctive depiction of Jesus, consistent with Coptic art. The Ethiopian Church, also Coptic, developed on Coptic traditions, but shows Jesus and all Biblical figures with the Ethiopian appearance of its members.[ commendation needed ] Other traditions in Asia and elsewhere also show the race of Jesus as that of the local population (encounter Chinese flick in the gallery below). In modern times such variation has get more than common, but images following the traditional depiction in both concrete appearance and clothing are still dominant, perhaps surprisingly then. In Europe, local ethnic tendencies in depictions of Jesus can exist seen, for instance in Spanish, High german, or Early Netherlandish painting, but almost always surrounding figures are notwithstanding more than strongly characterised. For example, the Virgin Mary, afterwards the vision reported past Bridget of Sweden, was oftentimes shown with blonde hair, but Christ's is very rarely paler than a lite brown.

Some medieval Western depictions, usually of the Meeting at Emmaus, where his disciples do not recognise him at showtime (Luke.24.thirteen–32), showed Jesus wearing a Jewish hat.[72]

The CGI model created in 2001 depicted Jesus' skin color every bit being darker and more olive-colored than his traditional depictions in Western art.

In 2001, the television series Son of God used one of three get-go-century Jewish skulls from a leading department of forensic scientific discipline in Israel to describe Jesus in a new mode.[73] A face was constructed using forensic anthropology by Richard Neave, a retired medical artist from the Unit of Art in Medicine at the University of Manchester.[74] The face that Neave constructed suggested that Jesus would take had a broad face and big nose, and differed significantly from the traditional depictions of Jesus in renaissance art.[75] Additional data nigh Jesus' pare color and hair was provided by Mark Goodacre, a New Testament scholar and professor at Duke Academy.[75]

Using tertiary-century images from a synagogue—the earliest pictures of Jewish people[76]—Goodacre proposed that Jesus' peel color would have been darker and swarthier than his traditional Western image. He besides suggested that he would take had short, curly hair and a short cropped beard.[77] Although entirely speculative as the face up of Jesus,[74] the upshot of the study adamant that Jesus' skin would have been more olive-colored than white or black,[75] and that he would accept looked similar a typical Galilean Semite. Amid the points made was that the Bible records that Jesus's disciple Judas had to bespeak him out to those arresting him in Gethsemane. The implied argument is that if Jesus's physical advent had differed markedly from his disciples, then he would have been relatively piece of cake to identify.[77]

Miraculous images of Jesus [edit]

There are, however, some images which have been claimed to realistically show how Jesus looked. One early on tradition, recorded by Eusebius of Caesarea, says that Jesus one time washed his confront with water and and then dried it with a cloth, leaving an image of his face imprinted on the cloth. This was sent by him to King Abgarus of Edessa, who had sent a messenger asking Jesus to come and heal him of his disease. This image, chosen the Mandylion or Paradigm of Edessa, appears in history in around 525. Numerous replicas of this "paradigm non made past human hands" remain in circulation. There are likewise icon compositions of Jesus and Mary that are traditionally believed past many Orthodox to have originated in paintings by Luke the Evangelist.

A currently familiar delineation is that on the Shroud of Turin, whose records become dorsum to 1353. Controversy surrounds the shroud and its exact origin remains subject to debate.[78] The Shroud of Turin is respected by Christians of several traditions, including Baptists, Catholics, Lutherans, Methodists, Orthodox, Pentecostals, and Presbyterians.[79] Information technology is one of the Catholic devotions canonical by state of the vatican city, that to the Holy Face of Jesus, at present uses the image of the face on the shroud as it appeared in the negative of the photograph taken by amateur lensman Secondo Pia in 1898.[80] [81] The image cannot be clearly seen on the shroud itself with the naked centre, and it surprised Pia to the extent that he said he near dropped and broke the photographic plate when he first saw the adult negative image on it in the evening of 28 May 1898.[81]

Earlier 1898, devotion to the Holy Confront of Jesus used an image based on the Veil of Veronica, where legend recounts that Veronica from Jerusalem encountered Jesus along the Via Dolorosa on the way to Calvary. When she paused to wipe the sweat from Jesus'south face with her veil, the prototype was imprinted on the textile. The establishment of these images equally Cosmic devotions traces dorsum to Sister Marie of St Peter and the Venerable Leo Dupont who started and promoted them from 1844 to 1874 in Tours France, and Sister Maria Pierina De Micheli who associated the image from the Shroud of Turin with the devotion in 1936 in Milan Italy.

"The Saviour Not Made by Hands", a Novgorodian icon from c. 1100 based on a Byzantine model

A very pop 20th-century depiction amongst Roman Catholics and Anglicans is the Divine Mercy image,[82] which was canonical by Pope John Paul Ii in April 2000.[83] The Divine Mercy depiction is formally used in celebrations of Divine Mercy Sunday and is venerated by over 100 meg Catholics who follow the devotion.[67] The image is not part of Acheiropoieta in that information technology has been depicted by modernistic artists, but the pattern of the paradigm is said to take been miraculously shown to Saint Faustina Kowalska in a vision of Jesus in 1931 in Płock, Poland.[83] Faustina wrote in her diary that Jesus appeared to her and asked her to "Paint an paradigm co-ordinate to the pattern you see".[83] [84] Faustina eventually institute an artist (Eugene Kazimierowski) to depict the Divine Mercy epitome of Jesus with his correct paw raised in a sign of blessing and the left hand touching the garment near his chest, with 2 large rays, 1 red, the other white emanating from well-nigh his center.[84] [85] Afterward Faustina's death, a number of other artists painted the prototype, with the delineation past Adolf Hyla being among the most reproduced.[86]

Warner Sallman stated that The Head of Christ was the result of a "miraculous vision that he received late one night", proclaiming that "the answer came at two A.M., January 1924" as "a vision in response to my prayer to God in a despairing situation."[87] The Head of Christ is venerated in the Coptic Orthodox Church,[88] after twelve-year-old Isaac Ayoub, who diagnosed with cancer, saw the optics of Jesus in the painting shedding tears; Fr. Ishaq Soliman of St. Mark's Coptic Church in Houston, on the same twenty-four hours, "testified to the miracles" and on the next day, "Dr. Atef Rizkalla, the family physician, examined the youth and certified that in that location were no traces of leukemia".[89] With episcopal approval from Bishop Tadros of Port Said and Bishop Yuhanna of Cairo, "Sallman's Head of Christ was exhibited in the Coptic Church", with "more than fifty one thousand people" visiting the church to run into information technology.[89] In addition, several religious magazines have explained the "power of Sallman'due south picture" by documenting occurrences such as headhunters letting become of a man of affairs and fleeing after seeing the image, a "thief who aborted his misdeed when he saw the Head of Christ on a living room wall", and deathbed conversions of non-believers to Christianity.[ninety] As an extraordinarily successful work of Christian pop devotional art,[91] information technology had been reproduced over half a billion times worldwide by the end of the 20th century.[92]

Controversies [edit]

The representation of Jesus has been controversial since the Synod of Elvira in 306 which states in the 36th canon that no worship image should be found in a church. [93]

In the 16th century, John Calvin and other Protestant reformers denounced the idolatry of images of Christ and called for their removal.[94] Due to their agreement of the second of the Ten Commandments, almost Evangelicals do not have a representation of Jesus in their places of worship.[95] [96]

Examples [edit]

-

A representation of Jesus riding in his chariot. Mosaic of the 3rd century on the Vatican grottoes under St. Peter'south Basilica.

-

Jesus depicted on an early eighth-century Byzantine coin. Subsequently the Byzantine iconoclasm all coins had Christ on them.

-

-

Reconstruction of the enthroned Jesus ( Yišō ) epitome on a Manichaean temple imprint from c. 10th-century Qocho (E Central Asia).

-

11th-century Christ Pantocrator with the halo in a cross form, used throughout the Middle Ages. Characteristically, he is portrayed as similar in features and skin tone to the culture of the artist.

-

"Christ All Mercy" Eastern Orthodox icon.

-

-

-

-

Palma il Vecchio, Head of Christ, 16th century, Italy

-

Jesus, aged 12, Jesus amid the Doctors (as a child debating in the temple), 1630 by Jusepe de Ribera.

-

-

Trevisani's depiction of the typical baptismal scene with the sky opening and the Holy Spirit descending every bit a dove, 1723.

-

19th-century Russian icon of Christ Pantocrator.

-

A nineteenth-century Chinese delineation of Jesus and the rich man, from Mark chapter 10.

-

A traditional Ethiopian delineation of Jesus and Mary with distinctively Ethiopian features.

-

-

-

Man dressed in Jesus costume.

Sculpture [edit]

-

-

-

-

-

-

Infant Jesus of Prague, one of several miniature statues of an infant Christ that are much venerated by the faithful

-

See besides [edit]

- Category:Cultural depictions of Jesus

- Crucifixion

- God the Father in Western art

- Holy card

- Ichthys

- Perceptions of religious imagery in natural phenomena

- Race of Jesus

- Resurrection of Jesus in Christian art

- Salvator Mundi

- Veil of Veronica

- Passion Play

- Christ figure

Notes [edit]

- ^ Philip Schaff commenting on Irenaeus, wrote, 'This censure of images as a Gnostic peculiarity, and as a heathenish corruption, should exist noted'. Footnote 300 on Contr. Her. .I.XXV.6. ANF

- ^ Synod of Elvira, 'Pictures are not to exist placed in churches, so that they do not get objects of worship and admiration', AD 306, Canon 36

- ^ Kitzinger, Ernst, "The Cult of Images in the Age before Iconoclasm", Dumbarton Oaks Papers, Vol. eight, (1954), pp. 83–150, Dumbarton Oaks, Trustees for Harvard Academy, JSTOR

- ^ "The Early Church building on the Aniconic Spectrum". The Westminster Theological Journal. 83 (1): 35–47. ISSN 0043-4388. Retrieved two March 2022.

- ^ Matthew xiv:46

- ^ Luke 8:43–44

- ^ Harold Westward. Attridge, Gohei Hata, et al. Eusebius, Christianity, and Judaism. Wayne, MI: Wayne State Academy Printing, 1992. pp. 283–284.

- ^ English translation institute at Catholic Academy of America, accessed v September 2012 [1]

- ^ John Calvin Institutes of the Christian Religion Volume i, Affiliate V. Section 6.

- ^ Hellemo, pp. iii–6, and Cartlidge and Elliott, 61 (Eusebius quotation) and passim. Clement approved the use of symbolic pictograms.

- ^ The Second Church: Pop Christianity A.D. 200–400 by Ramsay MacMullen, The Guild of Biblical Literature, 2009

- ^ McKay, John; Hill, Bennett (2011). A History of Globe Societies, Combined Book (9 ed.). United States: Macmillan. p. 166. ISBN978-0-312-66691-0 . Retrieved 5 August 2013.

- ^ Orpheus equally a symbol for David was already found in hellenized Jewish art. Hall, 66

- ^ Syndicus, 21–3

- ^ Cartlidge and Elliott, 53–55. See too The Two Faces of Jesus by Robin Grand. Jensen, Bible Review, 17.viii, October 2002, and Understanding Early Christian Fine art by Robin K. Jensen, Routledge, 2000

- ^ Hall, 70–71

- ^ Brandon, S.K.F, "Christ in verbal and depicted imagery". Neusner, Jacob (ed.): Christianity, Judaism and other Greco-Roman cults: Studies for Morton Smith at sixty. Part Two: Early Christianity, pp. 166–167. Brill, 1975. ISBN 978-90-04-04215-5

- ^ Zanker, 299

- ^ Every, George; Christian Mythology, p. 65, Hamlyn 1988 (1970 1st edn.) ISBN 0-600-34290-5

- ^ Syndicus, 92

- ^ Cartlidge and Elliott, 53 – this is Psalm 44 in the Latin Vulgate; English bible translations prefer "glory" and "majesty"

- ^ Zanker, 302.

- ^ Schiller, I 132. The image comes from the crypt of Lucina in the Catacombs_of_San_Callisto. There are a number of other 3rd-century images.

- ^ Painted over forty times in the catacombs of Rome, from the early on 3rd century on, and too on sarcophagii. As with the Baptism, some early examples are from Gaul. Schiller, I, 181

- ^ Syndicus, 94–95

- ^ Syndicus, 92–93, Catacomb images

- ^ "Catholic Encyclopedia: Portraits of the Apostles". Retrieved 10 August 2008.

- ^ Cartlidge and Elliott, lx

- ^ The Two Faces of Jesus past Robin M. Jensen, Bible Review, 17.8, Oct 2002

- ^ a b New Catholic Encyclopedia: Portraits of the Apostles

- ^ Jesus, the Magician by Morton Smith, Harper & Row, 1978

- ^ Zanker, 302

- ^ Zanker, 300–303, who is rather dismissive of other origins for the type

- ^ Syndicus, 93

- ^ Cartlidge and Elliott, 56–57. St Paul often has a long beard, simply short hair, as in the crypt fresco illustrated. St John the Baptist also often has long hair and a beard, and oftentimes retains in later on fine art the thick shaggy or wavy long pilus seen on some of the primeval depictions of Jesus, and in images of philosophers of the Charismatic blazon.

- ^ Zanker, 257–266 on the charismatics; 299–306 on the type used for Christ

- ^ Zanker, pp. 299, note 48, and 300. [2]. See also Cartlidge and Elliott, 55–61.

- ^ Grabar, 119

- ^ Zanker, 290

- ^ Syndicus, 92–97, though images of Christ the King are found in the previous century besides – Hellemo, 6

- ^ Hellemo, 7–fourteen, citing Grand. Berger in particular.

- ^ Zanker, 299. Zanker has a full account of the evolution of the image of Christ at pp. 289–307.

- ^ The two parts of the cycle are on opposite walls of the nave; Talbot Rice, 157. Bridgeman Library

- ^ "Last Judgment", Esperanca Camara, Khan Academy; Blunt Anthony, Artistic Theory in Italy, 1450–1600, 112–114, 118–119 [1940] (refs to 1985 edn), OUP, ISBN 0198810504

- ^ The Shroud of Christ ("marks") by Paul Vignon, Paul Tice, (2002 – ISBN ane-885395-96-5)

- ^ The Shroud of Christ ("Constantinople") by Paul Vignon, Paul Tice, op. cit.

- ^ Grigg, 5–7

- ^ Regarding the alternate NIV translation of 1 Corinthians 11:7, and in agreement with mod interpretations of the New Testament, Walvoord and Zuck note, "The alternate translation in the NIV margin, which interprets the homo's covering as long pilus, is largely based on the view that verse fifteen equated the covering with long pilus. It is unlikely, however, that this was the betoken of poesy 4." John F. Walvoord and Roy B. Zuck, eds., The Bible Noesis Commentary: New Testament, "1 Corinthians eleven:four", (Wheaton: Victor Books, 1983)

- ^ Establish for Classical Christian Studies (ICCS) and Thomas Oden, eds., The Ancient Christian Commentary Series, "1 Corinthians 1:iv", (Westmont: Inter-Varsity Press, 2005), ISBN 0-8308-2492-viii. Google Books

- ^ a b The New Westminster Dictionary of Church History by Robert Benedetto 2006 ISBN 0-8264-8011-X pp. 51–53

- ^ Jensen, Robin Chiliad. (2010). "Jesus in Christian art". In Burkett, Delbert (ed.). The Blackwell Companion to Jesus. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 477–502. ISBN978-i-4443-5175-0.

- ^ a b Iconography of Christian Fine art, Vol. I by Thousand. Schiller 1971 Lund Humphries, London. figs 150-53, 346-54. ISBN 0-85331-270-2 pp. 181–184

- ^ The paradigm of God the Father in Orthodox theology and iconography past Steven Bigham 1995 ISBN i-879038-15-3 pp. 226–227

- ^ Archimandrite Vasileios of Stavronikita, "Icons as Liturgical Analogies" in Hymn of entry: liturgy and life in the Orthodox church 1997 ISBN 978-0-88141-026-6 pp. 81–ninety

- ^ a b The paradigm of St Francis by Rosalind B. Brooke 2006 ISBN 0-521-78291-0 pp. 183–184

- ^ The tradition of Catholic prayer by Christian Raab, Harry Hagan, St. Meinrad Archabbey 2007 ISBN 0-8146-3184-3 pp. 86–87

- ^ a b The vitality of the Christian tradition by George Finger Thomas 1944 ISBN 0-8369-2378-2 pp. 110–112

- ^ La vida sacra: contemporary Hispanic sacramental theology by James L. Empereur, Eduardo Fernández 2006 ISBN 0-7425-5157-one pp. iii–5

- ^ Philippines by Lily Rose R. Tope, Detch P. Nonan-Mercado 2005 ISBN 0-7614-1475-4 p. 109

- ^ Experiencing Art Around U.s.a. by Thomas Buser 2005 ISBN 978-0-534-64114-6 pp. 382–383

- ^ Leonardo da Vinci, the Last Supper: a Cosmic Drama and an Act of Redemption by Michael Ladwein 2006 pp. 27, 60

- ^ Browne, Thomas. The Works of Thomas Browne Vol. two. Gutenberg.

- ^ Arthur Barnes, 2003 Holy Shroud of Turin Kessinger Printing ISBN 0-7661-3425-3 pp. two–9

- ^ William Meacham, The Authentication of the Turin Shroud:An Event in Archaeological Epistemology, Current Anthropology, Volume 24, No 3, June 1983

- ^ "Zenit, May five, 2010". Zenit.org. 5 May 2010. Archived from the original on 27 September 2012. Retrieved iv November 2011.

- ^ Catherine G. Odell, 1998, Faustina: Campaigner of Divine Mercy OSV Printing ISBN 978-0-87973-923-two p. 165

- ^ a b Am With You Ever past Benedict Groeschel 2010 ISBN 978-1-58617-257-2 p. 548

- ^ The Challenge of the Silver Screen (Studies in Organized religion and the Arts) Past Freek Fifty. Bakker 2009 ISBN 90-04-16861-3 p. one

- ^ Encyclopedia of early on cinema by Richard Abe 2005 ISBN 0-415-23440-9 p. 518

- ^ The Blackwell Companion to Jesus edited by Delbert Burkett 2010 ISBN 1-4051-9362-X p. 526

- ^ ""Super Size Me": Recognizing Jesus".

- ^ A 12th-century English language example is in the Getty Museum Archived 7 June 2010 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Wells, Matt (27 March 2001). "Is this the real confront of Jesus Christ?". The Guardian. London: Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. OCLC 60623878. Retrieved 12 May 2011.

- ^ a b Legon, Jeordan (25 December 2002). "From science and computers, a new face of Jesus". CNN. Retrieved 12 May 2011.

- ^ a b c Wilson, Giles (27 Oct 2004). "So what colour was Jesus?". BBC News. London. Retrieved 12 May 2011.

- ^ "Experts Reconstruct Confront Of Jesus". London: CBS. 27 March 2001. Retrieved 12 May 2011.

- ^ a b Fillon, Mike (7 December 2002). "The Real Face Of Jesus". Popular Mechanics. San Francisco: Hearst. ISSN 0032-4558. OCLC 3643271. Retrieved 12 May 2011.

- ^ William Meacham, The Authentication of the Turin Shroud: An Issue in Archaeological Epistemology, Current Anthropology, Volume 24, No iii, June 1983

- ^ The Rev. Albert R. Dreisbach (1997). "The Shroud of Turin: Its Ecumenical Implications".

Returning to the ecumenical dimension of this sacred linen, it became very evident to me on the nighttime of August 16, 1983, when local judicatory leaders offered their corporate approval to the TURIN SHROUD EXHIBIT and participated in the Evening Office of the Holy Shroud. The Greek Archbishop, the Roman Cosmic Archbishop, the Episcopal Bishop and the Presiding Bishop of the AME Church gathered before the world'due south first full size, backlit transparency of the Shroud and joined clergy representing the Assemblies of God, Baptists, Lutherans, Methodists and Presbyterians in an astonishing witness to ecumenical unity. At the determination of the service, His Grace Bishop John of the Greek Orthodox Diocese of Atlanta, turned to me and said: "Thank yous very much for picking our day." I didn't fully understand the significance of his remark until he explained to me that August 16th is the Banquet of the Holy Mandylion commemorating the occasion in 944 A.D. when the Shroud was first shown to the public in Byzantium post-obit its arrival the previous mean solar day from Edessa in southeastern Turkey.

- ^ Joan Carroll Cruz, 1984, Relics OSV Printing ISBN 0-87973-701-8 p. 49

- ^ a b Ann Ball, 2003 Encyclopedia of Cosmic Devotions and Practices ISBN 0-87973-910-Ten pp. 239, 635

- ^ Brockman, Norbert (2011). Encyclopedia of Sacred Places. ABC-CLIO. p. 140. ISBN978-one-59884-654-6.

- ^ a b c Tim Drake, 2002, Saints of the Jubilee, ISBN 978-1-4033-1009-5 pp. 85–95

- ^ a b A Divine Mercy Resource by Richard Torretto 2010 ISBN i-4502-3236-one "The Image of Divine Mercy" pp. 84–107

- ^ Catherine M. Odell, 1998, Faustina: Apostle of Divine Mercy OSV Press ISBN 978-0-87973-923-2 pp. 63–64

- ^ Butler'south lives of the saints: the third millennium by Paul Burns, Alban Butler 2001 ISBN 978-0-86012-383-5 p. 252

- ^ Morgan, David (1996). Icons of American Protestantism: The Art of Warner Sallman. Yale University Press. p. 62. ISBN978-0-300-06342-4.

Sallman ever insisted that his initial sketch of Jesus was the result of spiritual "picturization," a miraculous vision that he received late one night. "The reply came at 2 A.K., January 1924," he wrote. "It came as a vision in response to my prayer to God in a despairing situation." The situation was a deadline: Sallman had been deputed to paint the Feb cover for the Covenant Companion, the monthly magazine of the Evangelical Covenant Church building, and he had artist's block for weeks. The Feb outcome was focusing on Christian youth, and Sallman's assignment was to provide an inspirational image of Christ that would "challenge our young people." "I mused over information technology for a long time in prayer and meditation," Sallman recalled, "seeking for something which would take hold of the centre and convey the bulletin of the Christian gospel on the cover."

- ^ Otto F.A. Meinardus, Ph.D. (Fall 1997). "Theological Issues of the Coptic Orthodox Inculturation in Western Club". Coptic Church building Review. 18 (3). ISSN 0273-3269.

An interesting case of inculturation occurred on Monday, November xi, 1991 when the 12-year-old Isaac Ayoub of Houston, Texas, suffering from leukemia, saw that the optics of Jesus in the famous Sallman Head of Christ began moving and shedding an oily liquid like tears. On the aforementioned day, Fr. Ishaq Soliman, the Coptic priest of St. Mark'south Coptic Church in Houston, testified to the miracles. On the following day, Dr. Atef Rizkalla, the family unit dr., examined the youth and certified that there were no traces of leukemia. Sallman's Head of Christ was exhibited in the Coptic Church building and more than l,000 people visited the church. Two Coptic bishops, Anbâ Tadros of Port Said and Anbâ Yuhanna of Cairo verified the story.

- ^ a b Meinardus, Otto F. A. (2006). Christians In Egypt: Orthodox, Cosmic, and Protestant Communities – By and Present. American University in Cairo Press. p. seventy. ISBN978-one-61797-262-1.

An interesting case of inculturation took place on Monday, November eleven, 1991 when the twelve-twelvemonth-old Isaac Ayoub of Houston, Texas, suffering from leukemia, saw that the optics of Jesus in the famous Sallman "Head of Christ" began moving and shedding an oily liquid like tears. On the same day, Male parent Ishaq Soliman, the Coptic priest of St. Mark's Coptic Church building in Houston, testified to the miracles. On the following twenty-four hours, Dr. Atef Rizkalla, the family physician, examined the youth and certified that there were no traces of leukemia. Sallman's Head of Christ was exhibited in the Coptic Church building and more than than 50 thousand people visited the church. Ii Coptic bishops, Bishop Tadros of Port Said and Bishop Yuhanna of Cairo, verified the story.

- ^ Morgan, David (1996). The Fine art of Warner Sallman. Yale University Press. p. 192. ISBN978-0-300-06342-4.

Articles published in popular religious magazines during this fourth dimension gathered together in an evidently didactic way several anecdotes concerning the power of Sallman's moving-picture show amid nonwhites, non-Christians, and those exhibiting unacceptable behavior. We read of a white man of affairs, for instance, in a remote jungle, assaulted by a cruel group of headhunters who need that he remove his clothes. In going through his billfold, they discover a modest reproduction of Sallman's Christ, quickly apologize, then vanish "into the jungle without inflicting further damage." A 2d article relates the story of the thief who aborted his misdeed when he saw the Head of Christ on a living room wall. Another tells of the conversion of a Jewish woman on her deathbed, when a hospital clergyman shows her Sallman'southward picture.

- ^ Lippy, Charles H. (1994). Existence Religious, American Fashion: A History of Popular Religiosity in the The states. Greenwood Publishing Grouping. p. 185. ISBN978-0-313-27895-ii . Retrieved 30 April 2014.

Of these one stands out as having securely impressed itself of the American religious consciousness: the Head of Christ by artist Warner Sallman (1892–1968). Originally sketched in charcoal equally a cover illustration for the Covenant Companion, the mag of the Swedish Evangelical Mission Covenant of America denomination, and based on an paradigm of Jesus in a painting past the French artist Leon Augustin Lhermitte, Sallman'southward Head of Christ was painted in 1940. In half a century, information technology had been produced more than than five hundred million times in formats ranging from large-scale copies for use in churches to wallet-sized ones that individuals could carry with them at all times.

- ^ Blum, Edward J.; Harvey, Paul (2012). Color of Christ. UNC Press Books. p. 211. ISBN978-0-8078-3737-5 . Retrieved xxx Apr 2014.

By the 1990s, Sallman's Head of Christ had been printed more than 500 million times and had accomplished global iconic status.

- ^ Lisa Maurice, Screening Divinity, Edinburgh Academy Printing, Scotland, 2019, p. 30

- ^ Robin M. Jensen, The Cantankerous: History, Art, and Controversy, Harvard Academy Press, USA, 2017, p. 185

- ^ Cameron J. Anderson, The Faithful Artist: A Vision for Evangelicalism and the Arts, InterVarsity Printing, USA, 2016, p. 124

- ^ Doug Jones, Sound of Worship, Taylor & Francis, USA, 2013, p. 90

- ^ "Structure progressing on new Jesus statue along I-75". WCPO. xv June 2012. Archived from the original on 29 June 2013. Retrieved 7 September 2012.

References [edit]

- Cartlidge, David R., and Elliott, J.K.. Fine art and the Christian Apocrypha, Routledge, 2001, ISBN 978-0-415-23392-seven, Google books

- Every, George; Christian Mythology, Hamlyn 1988 (1970 1st edn.) ISBN 0-600-34290-5

- Grabar, André; Christian iconography: a study of its origins, Taylor & Francis, 1968, ISBN 978-0-7100-0605-9 Google books

- Grigg, Robert, "Byzantine Credulity as an Impediment to Antiquarianism", Gesta, Vol. 26, No. one (1987), pp. 3–9, The University of Chicago Printing on behalf of the International Center of Medieval Art, JSTOR

- James Hall, A History of Ideas and Images in Italian Art, 1983, John Murray, London, ISBN 0-7195-3971-4

- Hellemo, Geir. Adventus Domini: eschatological thought in 4th-century apses and catecheses. Brill; 1989. ISBN 978-90-04-08836-8.

- Yard Schiller, Iconography of Christian Art, Vol. I, 1971 (English trans from German), Lund Humphries, London, ISBN 0-85331-270-ii

- Eduard Syndicus; Early Christian Art; Burns & Oates, London, 1962[ ISBN missing ]

- David Talbot Rice, Byzantine Fine art, 3rd edn 1968, Penguin Books Ltd[ ISBN missing ]

- Zanker, Paul. de:Paul Zanker. The Mask of Socrates, The Image of the Intellectual in Antiquity, University of California Press, 1995 Online Scholarship editions

External links [edit]

- Pictures of Jesus Mayhap Derived from the Shroud of Turin December 2005

- Warner Sallman'due south Caput of Christ: An American Icon

- Is this the real face of Jesus Christ?

- Images of Christ – the Deesis Mosaic of Hagia Sophia

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Depiction_of_Jesus

0 Response to "Sketch Art Images How Do I Become a Christian"

Post a Comment